I Request You to Read This Post

Several weeks ago, I tweeted about a weird construction that I see frequently at work thanks to our project management system. Whenever someone assigns me to a project, I get an email like the one below:![Hi Jonathon, [Name Redacted] just requested you to work on Editing. It's all yours.](https://www.arrantpedantry.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Screen-Shot-2018-06-06-at-12.12.18-PM.png)

I said that the construction sounded ungrammatical to me—you can ask someone to do something or request that they do it, but not request them to do it. Several people agreed with me, while others said that it makes sense to them if you stress you—they requested me to work on it, not someone else. Honestly, I’m not sure that stress changes anything, since the question is about what kind of complementation the verb request allows. Changing the stress doesn’t change the syntax.

However, Jesse Sheidlower, a former editor for The Oxford English Dictionary, quickly pointed out that the first sense of request in the OED is “to ask (a person), esp. in a polite or formal manner, to do something.” There are citations from around 1485 down to the present illustrating the construction request [someone] to [verb]. (Sense 3 is the request that [someone] [verb] construction, which has been around from 1554 to the present.) Jordan Smith, a linguistics PhD student at Iowa State, also pointed out that The Longman Grammar says that request is attested in the pattern [verb + NP + to-clause], just like ask. He agreed that it sounds odd, though.

So obviously the construction has been around for a while, and it’s apparently still around, but that didn’t explain why it sounds weird to me. I decided to do a little digging in the BYU corpora, and what I found was a little surprising.

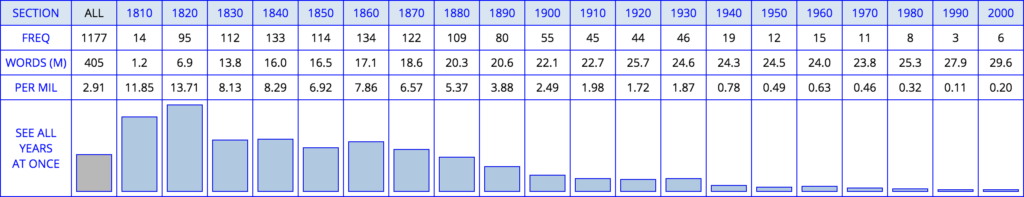

The Corpus of Historical American English (COHA) shows a slow decline in the request [someone] to [verb] construction, from 13.71 hits per million words in the 1820s to just .2 per million words in the first decade of the 2000s.

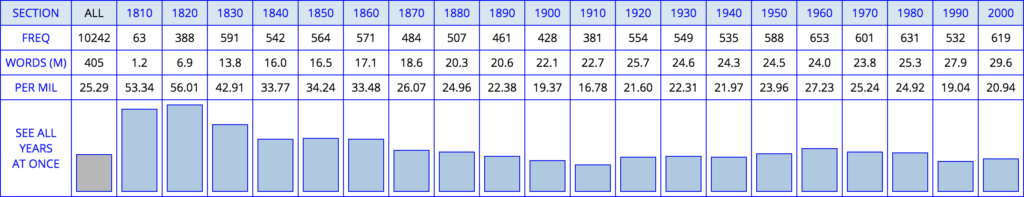

And it isn’t just that we’re using the verb request a lot less now than we were two hundred years ago. Though it has seen a moderate decline, it doesn’t match the curve for that particular construction.

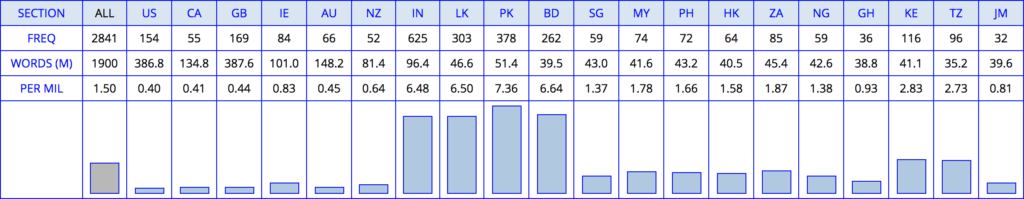

Even if the construction hasn’t vanished entirely, it’s pretty close to nonexistent in modern published writing—at least in some parts of the world. The Corpus of Global Web-Based English (GLoWbE) shows that while it’s mostly gone in nations where English is the most widely spoken first language (the US, Canada, the UK, Ireland, Australia, and New Zealand), it’s alive and well in South Asia (the taller bars in the middle are India, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, and Bangladesh). (Interestingly, the only OED citation for this construction in the last fifty years comes from a book called World Food: India.) To a lesser extent, it also survives in some parts of Africa and Southeast Asia (the two smallish bars at the right are Kenya and Tanzania).

It’s not clear why my work’s project management system uses a construction that is all but extinct in most varieties of English but is still alive and well in South Asia. The company is based in Utah, but it’s possible that they employ people from South Asia or that whoever wrote that text just happens to be among the few speakers of American English who still use it.

Whatever the reason, it’s an interesting example of language change in action. Peter Sokolowski, an editor for Merriam-Webster, likes to say, “Most English speakers accept the fact that the language changes over time, but don’t accept the changes made in their own time.” With apologies to Peter, I don’t think this is quite right. The changes we don’t accept are generally the ones made in our own time, but most changes happen without us really noticing. Constructions like request that [someone] [verb] fade out of use, and no one bemoans their loss. Other changes, like the shift from infinitives to gerunds and the others listed in this article by Arika Okrent, creep in without anyone getting worked up about them. It’s only the tip of the iceberg that we occasionally gripe about, while the vast bulk of language change slips by unnoticed.

This is important because we often conflate change and error—that is, we think that language changes begin as errors that gradually become accepted. For example, Bryan Garner’s entire Language Change Index is predicated on the notion that change is synonymous with error. But many things that are often considered wrong—towards, less with count nouns, which used as a restrictive relative pronoun—are quite old, while the rules forbidding their use are in fact the innovations. It’s perverse to call these changes that are creeping in when they’re really old features that are being pushed out. Indeed, the whole purpose of the index isn’t to tell you where a particular use falls on a scale of change, but to tell you how accepted that use is—that is, how much of an error it is.

So the next time you assume that a certain form must be a recent change because it’s disfavored, I request you to reexamine your assumptions. Language change is much more subtle and much more complex than you may think.

John Boyd

Jonathon, this was interesting to read. Thank you. I’m a freelance writer and would like to learn how to use such language tools as the examples of corpus use you site. Can you recommend anything that would get me started?

Jonathon Owen

Thanks! I’m glad you liked it. I don’t think there are a lot of good resources aimed at non-linguists, but this free ebook looks useful. I’ve also presented at conferences a couple of times on using corpora, and you can look at my slides here. They might be hard to follow by themselves, though.

Catherone Sommer

My understanding from my early English grammar lessons is that if the direct object can become the subject in the passive voice, the verb can be used in the active voice with the construction direct object + to + infinitive – e.g. He gave her a present -> she was given a present. The passive construction with request is still quite common in British English, e.g. “Passengers are requested not to smoke in the lavatories” so presumably the converse is also true, and one could say “We request you not to smoke …”. Not a construction that has ever struck me as unusual or weird, but then I’m an Ancient Briton and something of a linguistic fossil! Maybe the high incidence of Indians and Pakistanis has kept the construction alive in my part of England?

Jonathon Owen

That’s interesting—I hadn’t thought about passive forms. It looks like they mostly follow the same pattern as the active forms, but the differences aren’t quite as clear-cut. I don’t think it’s as simple as Indians and Pakistanis keeping it alive in England, but I’m not quite sure what’s going on there.

David Chamberlain

Insofar as your project management system is concerned, I would not be surprised to learn the software was coded offshore (in India or Pakistan). There is a tendency in my experience to assume developers there speak English as a 1st language, and there is, for that reason, not to check the English in such projects carefully.

As we all know, though, the versions of English spoken in Canada, the UK, South Africa, Australia, New Zealand, and the US are not precisely the same. The same holds true for India and Pakistan. (My usual example is the Indian used of “today morning” to mean “this morning”).

That may be part of what is happening with your PM system.

Phil

Very interesting, Jonathon. I agree (from a British perspective) that ‘X requested you to do Y’ sounds a little awkward; but (1) ‘X requested that you do Y’ also sounds somewhat stilted to me and (2) Catherine’s ‘Passengers are requested not to smoke’ seems OK (if pompous). This illustrates something that I constantly come up against as a translator: constructions and ways of saying things may be technically OK, but still not ‘sound right’. (I suspect this is a characteristic of modern English, and that speakers of the language in Shakespeare’s day felt far less constrained, incidentally, but I can’t back that up.)

Like John, I can see the value of consulting these corpora, as one of the main failings of standard dictionaries (of English and the other languages I work with) is that they rarely give any indication of the frequency of use of the words they define or the possible senses that they suggest.

Charles Perrine

It seems to me that there’s an interesting and somewhat surprising oversight in interpretation here. For context, I’m an early / obsessive / chronic reader with no tertiary education and some history of success in freelance copy editing (Chicago) and transcription. On top of having received money from people before, I also have ops in ##English, in case you were looking for further incontrovertible proof that I know what I’m talking about.

Seriously though, I find myself hesitant to point this out for fear that I’m just Dunning-Krugering myself (again), but I’m reading another interpretation. Maybe it isn’t a significant one.

The sentence can understandably offend the Sprachgefühl if you try to reconcile it as a complex catenative construction parallel to “requested [that] you {[bare] ɪɴғ}”. but it seems to work nicely in contemporary English if “to work on Editing” is a shortened form of “in order to work on Editing”, “so as to . . .”, etc.

This raises a small discrepancy in agency — they aren’t requesting you in order that they themselves might work on Editing (unless maybe this person really does think you’re a tool). It’s easy enough to massage into making sense if you loosen the interpretation slightly to allow “for the purpose of working on Editing” (as a natural extrapolation from “in order to”) or “that you might work on Editing”.

The thought occurred to me that this might be considered a meaningless distinction on grounds that even as the complement of an implied “in order [to]”, “[to] work” is still an infinitive, and there’s no real basis for differentiating “requested you to work” as “requested of you to work” from “requested you to work” as “requested you for to work” (which *seems* like a great way to concisely express that, but turns out to *also* be a generic infinitive marker, go figure). But it seems like there would be material differences in how they diagram and what arguments they can take. In the former case, “to work …” begins a verb phrase, while in the latter it begins a prepositional phrase and can be preceded by another one; e.g., “requested you from your supervisor to work on Editing” (a nearly similar construction is allowed by the former, though it seems to want a parenthetical like “requested you, via your supervisor, to work on Editing”).

Thoughts? It seems like something that someone else would have thought of already if it were considered a substantive distinction, but it also seems that it arguably is one.