Sorry, Merriam-Webster, but Hot Dogs Are Not Sandwiches

On the Friday before Memorial Day, Merriam-Webster sent out this tweet:

Have a great #MemorialDayWeekend. The hot dog is a sandwich. https://t.co/KeNiTAxPAm

— Merriam-Webster (@MerriamWebster) May 27, 2016

They linked to this post describing ten different kinds of sandwiches and asserted that “yes, the hot dog is one of them.” They say,

We know: the idea that a hot dog is a sandwich is heresy to some of you. But given that the definition of sandwich is “two or more slices of bread or a split roll having a filling in between,” there is no sensible way around it. If you want a meatball sandwich on a split roll to be a kind of sandwich, then you have to accept that a hot dog is also a kind of sandwich.

Predictably, the internet exploded.

Users took to Twitter with the hashtag #hotdogisnotasandwich to voice their disagreement. Numerous Twitter polls showed that anywhere from 75 to 90 percent of respondents agreed that the hot dog is not a sandwich. Meanwhile, Merriam-Webster’s Emily Brewster went on the podcast Judge John Hodgman to defend Merriam-Webster’s case. Part of her argument is that there’s historical evidence for the sandwich definition: in the early to mid-twentieth century, hot dogs were commonly called “hot dog sandwiches”. Jimmy Kimmel, on the other hand took to his podium to make a more common-sense appeal:

Is a hot dog a sandwich? #Kimmel4VPOMGhttps://t.co/05HU3DsKw6

— Jimmy Kimmel (@jimmykimmel) June 1, 2016

That’s their definition. By my definition, a hot dog is a hot dog. It’s its own thing, with its own specialized bun. If you went in a restaurant and ordered a meat tube sandwich, would that make sense? No! They’d probably call the cops on you. I don’t care what anyone says—a hot dog is not a sandwich. And if hot dogs are sandwiches, then cereal is soup. Chew on that one for a while.

For reference, here’s Merriam-Webster’s definition of soup:

1 : a liquid food especially with a meat, fish, or vegetable stock as a base and often containing pieces of solid food

Read broadly, this definition does not exclude cold cereal from being a type of soup. Cereal is a liquid food containing pieces of solid food. It doesn’t have a meat, fish, or vegetable stock as a base, but the definition doesn’t strictly require that.

But we all know, of course, that cereal isn’t soup. Soup is usually (but not always) served hot, and it’s usually (but again, not always) savory or salty. It’s also usually eaten for lunch or dinner, while cereal is usually eaten for breakfast. But note how hard it is to write a definition that includes all things that are soup and excludes all things that aren’t.

My friend Mike Sakasegawa also noted the difficulty in writing a satisfactory definition of sandwich, saying, “Though it led me to the observation that sandwiches are like porn: you know it when you see it.” I said that this is key: “Just because you can’t write a single definition that includes all sandwiches and excludes all not-sandwiches doesn’t mean that the sandwich-like not-sandwiches are now sandwiches.” And Jesse Sheidlower, a former editor for the Oxford English Dictionary, concurred: “IOW, Lexicographer Fail.”

I wouldn’t put it that way, but, with apologies to my good friends at Merriam-Webster, I do think this is a case of reasoning from the definition. Lexicography’s primary aim is to describe how people use words, and people simply don’t use the word sandwich to refer to hot dogs. If someone said, “I’m making sandwiches—what kind would you like?” and you answered, “Hot dog, please,” they’d probably respond, “No, I’m making sandwiches, not hot dogs.” Whatever the history of the term, hot dogs are not considered sandwiches anymore. Use determines the definition, not the other way around. And definitions are by nature imperfect, unless you want to make them so long and detailed that they become encyclopedia entries.

So how can hot dogs fit the description of a sandwich but not be sandwiches? Easy. I propose that sandwiches are a paraphyletic group. A monophyletic group contains all the descendants of a common ancestor, but a paraphyletic group contains all descendants of a common ancestor with some exceptions. In biology, for example, mammals are a monophyletic group, because they contain all the descendants of the original proto-mammal. Reptiles, on the other hand, are an example of a paraphyletic group—the common ancestor of all reptiles is also the common ancestor of birds and mammals, but birds and mammals are not considered reptiles. Thus a chart showing the phylogenetic tree of reptiles has a couple of scallops cut out to exclude those branches. (Edited to add: The ancestors of mammals were traditionally considered reptiles, but they’re now considered to be a separate branch, as shown in this figure.)

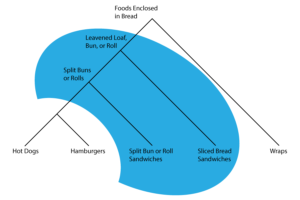

Foods may not have ancestors in the same sense, but we can still construct a sort of phylogeny of sandwiches. Sandwiches include at least two main groups—those made with slices of bread and those made with a split bun or roll. Hot dogs would normally fall under the split-bun group, but instead they form their own separate category.

Note that this sort of model is also quite flexible. Some people might consider gyros or shawarma sandwiches, but I would consider them a type of wrap. Some people might also consider hamburgers sandwiches but not hot dogs. Sloppy joes and loose meat sandwiches may be edge cases, falling somewhere between hamburgers and more traditional split-roll sandwiches. And in some countries, people might also say that the split-bun types aren’t sandwiches, preferring to simply call these rolls.

Wherever you draw the line, the important thing is that you can draw the line. Don’t let the dictionary boss you around, especially on such an important topic as sandwiches.

Chips Mackinolty

I’m sorry Merriam-Webster: perfectly happy to regard you as an authority on many things, but the hot dog as a sandwich? At least from an Australian perspective this is just not on–especially as we Aussies would regard the hot dog as a north American dietary innovation. And a long way from its supposed progenitor John Montagu, the 4th Earl of Sandwich. FFS! The whole point is that the hot dog is definitively NOT a sandwich. It is what it is, sui generis!

Karen

Ummm. Cereal can be eaten without liquid JUST FINE. Many people never pour milk over their cereal. Is the liquid optional for soup? I don’t think so. /anti-soggy-cereal rant

Jonathon Owen

Much as “hot dog” can mean the sausage or the whole sausage-in-a-bun-with-toppings concoction, I think “cereal” can mean by “dry cereal” and “cereal in milk”. You can eat a hot dog without a bun just fine, and obviously that’s not a sandwich. Similarly, dry cereal is obviously not soup (and I don’t think cereal in milk is really soup either, in case that wasn’t clear).

steven wiliamson

Sorry Karen…everything in soup can also be eaten without liquid…

hmf

You’ve convinced me.

Cereal is a soup.

Jonathon Owen

Then my work here is done.

ablestmage

The biggest problem with this article is that it completely misunderstands M-W’s position on the issue. M-W is not proposing that, prescriptively, a hot dog is a sandwich or the reverse, because dictionaries do not even do this to begin with.

Think of a twitter hash tag search. If you search for a particular hash tag, Twitter will bring up results of the ways that hashtag has been OBSERVED (description) to have been used, but does not propose restrictions (prescription) on the limited ways that a hashtag is ALLOWED to be used. Dictionary researchers observe the way words are used by the ordinary person, and then compile the way the ordinary person uses words statistically. The ranking within a particular dictionary entry, such as “1. n. a thing, 2. n. another thing,” is a ranking of the tallies in which a word has been OBSERVED to have been used, in decreasing order of frequency. The dictionary is not saying that you are only allowed to use a word in this fashion, or that it must be pronounced/etc this way in order to be correct, but merely that the largest number of observations about the general public’s use of the word is ranked in this order. A dictionary does not PRESCRIBE usage, it DESCRIBES usage.

Think of a newspaper reporting on a murder, or the score of a sporting event. The newspaper is not insisting that all future murders be conducted in this fashion, nor that all future sporting events between these teams must result in the same score. Even if they list multiple games between the same teams, the newspaper is not imposing a rule that future games must be influenced by the average score. Likewise, a dictionary is simply describing the ways the largest numbers of people have been observed to use a word.

Think of sports, if you’re into that. Asking, “is a hot dog a sandwich?” of a dictionary is like asking “am I allowed to touch the ball with my hands?” of sports in general. If you were to compile the answers to this question, when asked of all sports, you might get the first entry as “yes” if more sports allowed or permitted players to touch the ball with their hands, but it would not answer for which sport, since “yes” would be the answer to more sports that did allow it than sports that didn’t. Likewise, the entry ranking for a dictionary entry is not based on context, it is merely a statistical ranking of the ways that a word is observed to be used. You would need to specify which sport in particular, in order to get the context you’re after. English is like the category of sports. There are individual styles of English that have rules, but English itself does not. It is correct in Associated Press style to hypenate eight-year-old, but not in Strunk & White’s Manual of Style. The style you learned in school applied to passing that class, not to English in general, just the same as learning and grading on a particular kind of brush stroke for an art class doesn’t restrict the validity of other kinds of brush strokes in art in general.

There was a big to-do about how dictionary entries for “marriage” were updated to include unions between other couples than simply man and woman, and the people who don’t understand how dictionaries work got upset because they believed dictionary publishers were bowing to political pressure when they should have been more scientific — except dictionaries ARE being scientific about it, since the entry for words reflects observations about how frequently the general public uses words, without establishing a correctness or incorrectness. The people who believed the dictionaries were bowing to political pressure did not even grasp the nature of a dictionary to begin with, falsely believing that dictionaries established a rule system by which all usage must be measured against, when rather actually dictionaries merely publish statistical data on how the general public is observed to use it, ranked by ‘most often observed’ down to an arbitrary threshold of ‘often enough to be included in our list.’

If you want to use spoons as a percussion instrument, by all means do so, but do not for one moment insist that all spoons were created for that purpose. Likewise, a dictionary can be used as a word bank for Scrabble, or as a kind of guide by which those who wish to tailor their writing so that only the most common usages of words are used in order to more efficiently express intent whilst minimizing questions about intent — but that is not made for that. As M-W’s own FAQ puts it: authoritative without authoritarianism.

ablestmage

Further, a “definition” of a dictionary is not a “defined” way to use a word in the sense that it must be used that way, or that the way listed is “acceptable” because a dictionary does not propose acceptability or unacceptability. If you’re using a dictionary to look up “definition” and find that a statistically significant number of people observed use the word when they are trying to express the ‘entry in a dictionary’ then you’re using circular reasoning — the dictionary is instead merely describing, still, that the largest numbers of people use ‘definition’ when they intend to mean ‘entry in a dictionary.’

Jonathon Owen

Actually, I think I understand M-W’s position quite well. I’m well aware that dictionaries describe rather than prescribe usage, and that’s precisely why I take issue with their declaring the hot dog a sandwich.

This declaration is based not on observed usage but on the definition itself. Their argument was “a split bun with filling is a sandwich; ergo, a hot dog is a sandwich”, not “people call a hot dog a sandwich; ergo, our definition of sandwich includes hot dogs”. And it was an argument, not a statement of fact; I’m sure they’re well aware that almost nobody calls hot dogs sandwiches, but they were essentially saying that everyone should consider it a sandwich because it fits a certain arbitrary (and quite broad) definition.

That’s not a description, because it’s not based on facts. There are no relevant hits for “hot dog sandwich” in the Corpus of Contemporary American English (the one hit is just a list of menu items, not a genuine collocation), and the phrase in Google Books Ngrams is vanishingly rare compared to “hot dog” by itself. I don’t think this scant evidence is enough to conclude that English speakers use the term sandwich to include hot dogs.

Mike McKay

The “hot” dog, was coined for it’s ability to hold a hot piece of meat between a heat barrier; in this case, a bun.

David Morris

I would not classify a split bun or roll as a sandwich, so a fortiori would not classify a hot dog as one.

panoptical

I would argue that “hot dog” refers exclusively to the meat (which, as someone else observed, can be eaten with or without bread. If you ask a grocer for hot dogs they will give you a pack of hot dogs, not a pack of hot dogs and a pack of hot dog buns. So clearly a hot dog isn’t a sandwich.

On the other hand, it is conventional for a hot dog to be *served* on a bun, and the hot dog + bun combo could properly be called a sandwich, but we don’t have a separate name for the dog+bun combo so we just refer to it as a hot dog. Initially this was called a “hot dog sandwich” but it was shortened to just “hot dog” because the convention became so strong that the “sandwich” part was extraneous.