Over Has Always Meant More Than. Get Over it.

Last month, at the yearly conference of the American Copy Editors Society, the editors of the AP Stylebook announced that over in the sense of more than was now acceptable. For decades, newspaper copy editors had been changing constructions like over three hundred people to more than three hundred people; now, with a word from AP’s top editors, that rule was being abandoned.

According to Merriam-Webster editor Peter Sokolowski, who was in attendance, the announcement was met with gasps. Editors quickly took to Twitter and to blogs to express their approval or dismay. Some saw it as part of the dumbing-down of the language or as a tacit admission that newspapers no longer have the resources to maintain their standards. Others saw it as the banishment of a baseless superstition that has wasted copy editors’ time without improving the text.

The argument had been that over must refer to spatial relationships and that numerical relationships must use more than. But nobody objects to other figurative uses of over, such as over the weekend or get over it or in over your head or what’s come over you? The rule forbidding the use of over to mean more than was first codified in the 1800s, but over can be found in this sense going back a thousand years or more, in some of the earliest documents written in English.

Not only that, but parallel uses can be found in other Germanic languages, including German, Dutch, and Swedish. (Despite all its borrowings from French, Latin, and elsewhere, English is considered a Germanic language.) There’s nothing wrong with the German Kinder über 14 Jahre (children over 14 years) (to borrow an example from the Collins German-English Dictionary) or the Swedish Över femhundra kom (over five hundred came). This means that this use of over actually predates English and must have been inherited from the common ancestor of all the Germanic languages, Proto-Germanic, some two thousand years ago.

Mignon Fogarty, aka Grammar Girl, wrote that “no rationale exists for the ‘over can’t mean more than’ rule.” And in a post on the Merriam-Webster Unabridged blog, Sokolowski gave his own debunking, concluding that “we just don’t need artificial rules that do not promote the goal of clarity.” But none of this was good enough for some people. AP’s announcement caused a rift in the editing staff at Mashable, who debated the rule on the lifestyle blog.

Alex Hazlett argued that the rule “was an arbitrary style decision that had nothing to do with grammar, defensible only by that rationale of last resort: tradition.” Megan Hess, though, took an emotional and hyperbolic tack, claiming that following rules like this prevents the world from slipping into “a Lord of the Flies-esque dystopia.” From there her argument quickly becomes circular: “The distinction is one that distinguishes clean, precise language and attention to detail — and serves as a hallmark of a proper journalism training.” In other words, editors should follow the rule because they’ve been trained to follow the rule, and the rule is simply a mark of clean copy. And how do you know the copy is clean? Because it follows rules like this. As Sokolowski says, this is nothing more than a shibboleth—the distinction serves no purpose other than to distinguish those in the know from everyone else.

It’s also a perfect example of a mumpsimus. The story goes that an illiterate priest in the Middle Ages had learned to recite the Latin Eucharist wrong: instead of sumpsimus (Latin for “we have taken”), he said mumpsimus, which is not a Latin word at all. When someone finally told him that he’d been saying it wrong and that it should be sumpsimus, he responded that he would not trade his old mumpsimus for this person’s new sumpsimus. He didn’t just refuse to change—he refused to recognize that he was wrong and had always been wrong.

But so what if everyone’s been using over this way for longer than the English language has existed? Just because everyone does it doesn’t mean it’s right, right? Well, technically, yes, but let’s flip the question around: what makes it wrong to use over to mean more than? The fact that the over-haters have had such an emotional reaction is telling. It’s surprisingly easy to talk yourself into hating a particular word or phrase and to start judging everyone who allegedly misuses it. And once you’ve developed a visceral reaction to a perceived misuse, it’s hard to be persuaded that your feelings aren’t justified.

We editors take a lot of pride in our attention to language—which usually means our attention to the usage and grammar rules that we’ve been taught—so it can seem like a personal affront to be told that we were wrong and have always been wrong. Not only that, but it can shake our faith in other rules. If we were wrong about this, what else might we have been wrong about? But perhaps rather than priding ourselves on following the rules, we should pride ourselves on mastering them, which means learning how to tell the good rules from the bad.

Learning that you were wrong simply means that now you’re right, and that can only be a good thing.

Update: Parallel uses can also be found in cognates of over in other Indo-European languages. For instance, the Latin super could mean both “above” and “more than”, and so could the Ancient Greek ὑπέρ, or hyper. It’s possible that the development of sense from “above” to “more than” happened independently in Latin, Ancient Greek, and Proto-Germanic, but at the very least we can say that this sort of metaphorical extension of sense is very common and very old. There are no logical grounds for objecting to it.

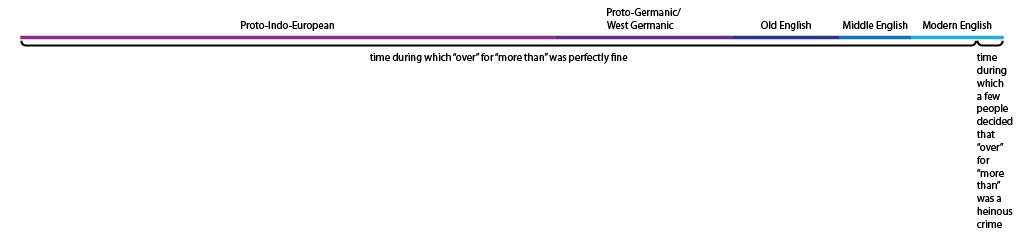

I also created this helpful (and slightly snarky) timeline of the usage of over and its etymons in English and its ancestor languages.

Catherine

In all my years of writing, translating, proofreading, editing and teaching English, I have never come across this ridiculous rule! Is it purely an American one? I can find no evidence of it in British usage or in prescriptive british English grammar books. And I have been speaking, writing, reading and listening to english for over 70 years!

Jonathon Owen

Yes, it is purely an American rule, and mostly an American journalism rule. Thankfully, it doesn’t seem to have caught on anywhere else.

Jonathon Owen

For the record, even Canadian editors are perplexed by this rule.

link

Jordan Smith

Really enjoyed this post. I found the comparison to other Germanic languages particularly interesting. Thanks for sharing!

n0aaa

So “under” slips under the radar?

Jonathon Owen

They pointed out when they made the announcement that this meant that under was also okay, so I assume they used to have a rule against that too.

Catherine

I apologise for my lack of capitals on British and English in my previous comment – bad eyesight and small print combined with perplexity over why such a rule should ever have been conceived in the first place!

Ian Martin

Many thanks for another entertaining insight esp. the Germanic roots. Are there any clues as to the origin of the ‘over’ rule e.g. which Manhattan cocktail party regurgitated this little gem for us all to choke on?

Jonathon Owen

Grammar Girl explains the origins better in her post. It was popularized in the late 1800s by the New York Evening Post editor William Cullen Bryant, but Jan Freeman found an earlier mention of the rule by Walton Burgess in 1856.

Warsaw Will

@Richard – “the history of English grammar began late in the sixteenth century” – one of the essential parts of grammar is syntax – how we string words together. If English grammar had indeed only started in the sixteenth century, people would have been unable to communicate. Did Old English and Middle English have no grammar? Do purely oral languages have no grammar?

It’s a strange idea that grammar only exists, or is only ‘correct’ when people start codifying it. It seems to me to be rather putting the cart before the horse!

In fact, the earliest grammar books such as Ben Jonson’s of around 1601, I think, didn’t try and make rules, but simply observed how the language worked. It was only with the publication of Robert Lowth’s ‘A Short Introduction to English Grammar’ in 1762 that we really get grammarians prescribing rules.

And what about Shakespeare? Can we not quote him as a source for grammatical constructions simply because he was writing before ‘the history of English grammar’ had begun?

Jonathon Owen

Richard: Yes, language evolves, but it doesn’t stand to reason that change must be good or bad. Linguistic change is simply change; it doesn’t have any inherent value.

But talking about change is kind of irrelevant here, because the point was that this hasn’t changed in thousands of years. It’s a stable feature of the language. On what grounds can we say that this use of over is somehow wrong? Any argument against it falls apart in one way or another. There’s no reason to grant the premise that it must be used spatially, because there are other non-spatial uses that aren’t considered wrong, and other prepositions that have a spatial meaning at their core are frequently used in non-spatial ways.

You can’t say that it’s wrong because the best writers avoid it or because educated speakers in formal settings avoid it, because they clearly don’t. Literally the only reason why you can say it’s wrong is because someone said it’s wrong and some other people wrote that down in a stylebook. To borrow from Kory Stamper’s presentation at ACES about usage dictionaries, I could tell you that chair is an ugly word and that you should never use it, but in the end that’s nothing more than my opinion.

Also, I’m not sure what passionate endeavors have to do with anything, nor do I think that Grammar Girl’s credentials should matter. The evidence and argument speak for themselves.

“Shakespeare is a creative writer and his writing is not expository. Why would we quote Shakespeare as a source for his grammatical construction?”

Why wouldn’t we? Why should only expository writing be cited as evidence? The language consists of far more than expository writing.

Warsaw Will

@Richard – William Bullokar’s book is certainly credited with being the first real English grammar for native speakers. I understand that he wanted to show that English had rules, just like Latin, but that doesn’t make him a prescriptivist. I teach (descriptive) grammar to foreign learners, and of course we accept that English is based on rules, but that those rules have evolved with the language, rather than being set in stone by grammar writers. As far as I know Bullokar is usually included with people like Ben Jonson as being ‘pre-prescriptive’. But as, unlike other early grammars, I’ve been unable to find it on the internet, I can’t really comment further than that.

Why Shakespeare? Why does Samuel Johnson illustrate his dictionary entries by quoting people like Shakespeare, Steele, Pope and Addison? Because he thought they represented the finest exponents of the language, no doubt.

“Grammar rules always existed, but as they became more codified correctness became an issue. ” – Exactly, but”correctness” according to whom? Writers of grammar books such as Ben Jonson and Joseph Priestley were largely content to observe actual usage, or in the latter’s case, base it on what he thought was the best use of the day. And they did indeed “explain, describe, or inform”. But the prescriptivists decided to take it further. And you might be surprised just how many of those more controversial rules were indeed based on someone’s whim, or what they found sounded better.

And going back to “over” for “more”. If it is such a golden rule, why is it, I wonder, that it seems to be have been largely confined to North America.

Jonathon Owen

Sure, it’s a different word, but this doesn’t meant that they can’t overlap in one sense.

Can you provide some evidence that it wasn’t? Because no justification is given in the earliest sources for this rule. If someone is going to propose a rule, the burden of proof should be on them to justify it.

So?

I already answered this: the facts and argument should speak for themselves. But the truth is that people do pay attention to authority, whether that authority is gained through formal means or not. When some random blogger says that it’s okay to use over to mean more than, people might not listen; when Grammar Girl says it (along with dictionary and stylebook editors and others with more formal authority), they’re more likely to take the argument seriously.

Why make such a big deal about his occasional unorthodox language? Evidence is evidence, and Shakespeare’s writings are certainly worthwhile evidence. All Warsaw Will was saying is that evidence from the time before rules were codified is still relevant. And why shouldn’t it be? The rules that have been handed down have often been based on individual preferences and often do not reflect English as it is used or ever has been used, even by the most prestigious writers.

You seem to be starting from the a priori assumption that if someone made a rule, they must have had a good reason for it, so you’re dismissing any evidence that would invalidate your assumption. If all this evidence doesn’t make it right, and if the arguments of dictionary editors, stylebook editors, and so-called “pop-up grammarians” doesn’t make it right, what would? What, in your opinion, makes a usage wrong? Can you describe a reliable method for distinguishing between linguistic right and wrong that doesn’t ultimately reduce to an ipse dixit?

Martyn Cornell

“just because a few people don’t want to learn the difference, or too lazy to employ the difference, it’s been decided, by a few, that it’s an irrelevancy.”

Nonsense. It’s clear the overwhelming majority of people – not “a few” – find differentiating between “who” and “whom” to be unnecessary to understanding, and therefore an irrelevancy, just the way the overwhelming majority back in the 16th century decided that differentiating between “ye” and “you” was unnecessary to understanding as well.